DOMINIKA WRÓBLEWSKA

APR 01, 2024

Zapraszamy do bardzo ciekawego artykułu Dominiki Wrøblewskiej o Gdańskim Klubie Morsów. Szczególną uwagę należy zwrócić na jej wspaniałe rysunki🤗👌 Spędziła z nami trochę czasu i uchwyciła, to w bardzo interesujący sposób. Obiecała, że w przyszłym sezonie wejdzie z nami do wody 😉💙 p.s artykuł jest po angielsku, więc jakby co pomocą służy tłumacz Google.

What 600 walruses were doing in costumes and bathing suits.

Poland comes out of winter slowly, especially in its northern parts. It wouldn’t be a huge surprise if snow decided to fall in April. Luckily, the Poles have a method to prevent this sort of incident. In a ritual that reaches far back to the pagan times of Slavic gods and goddesses, an effigy that represents Marzanna, the Slavic goddess of winter and death, is built out of straw, cloth and ribbons, then thrust into a lake and drowned. Often, it is also set on fire, and then drowned, just to be double sure it doesn’t come back to life. Marzanna is dead, winter is dead; bring on the spring.

It’s the morning of March 24, and I am witnessing the drowning of Marzanna in Sopot, a seaside resort town just north of Gdańsk.

More than 600 swimmers have come from all over the country to say goodbye to winter by plunging into the cold waters of the Baltic Sea. They are carrying flags, banners and colorful Marzannas. Many here are dressed as Marzannas themselves, with wreaths in their hair and straw-like dresses.

The Walruses

The term “walrus,” or “mors” in Polish, describes a person who practices winter swimming or bathing in a cold body of water, be it the sea or a river or lake. On this side of the Baltic, the season begins in October and ends in April.

My first close encounter with the walruses was back in February at Jelitkowo Beach, which is closer to my home in Gdansk.

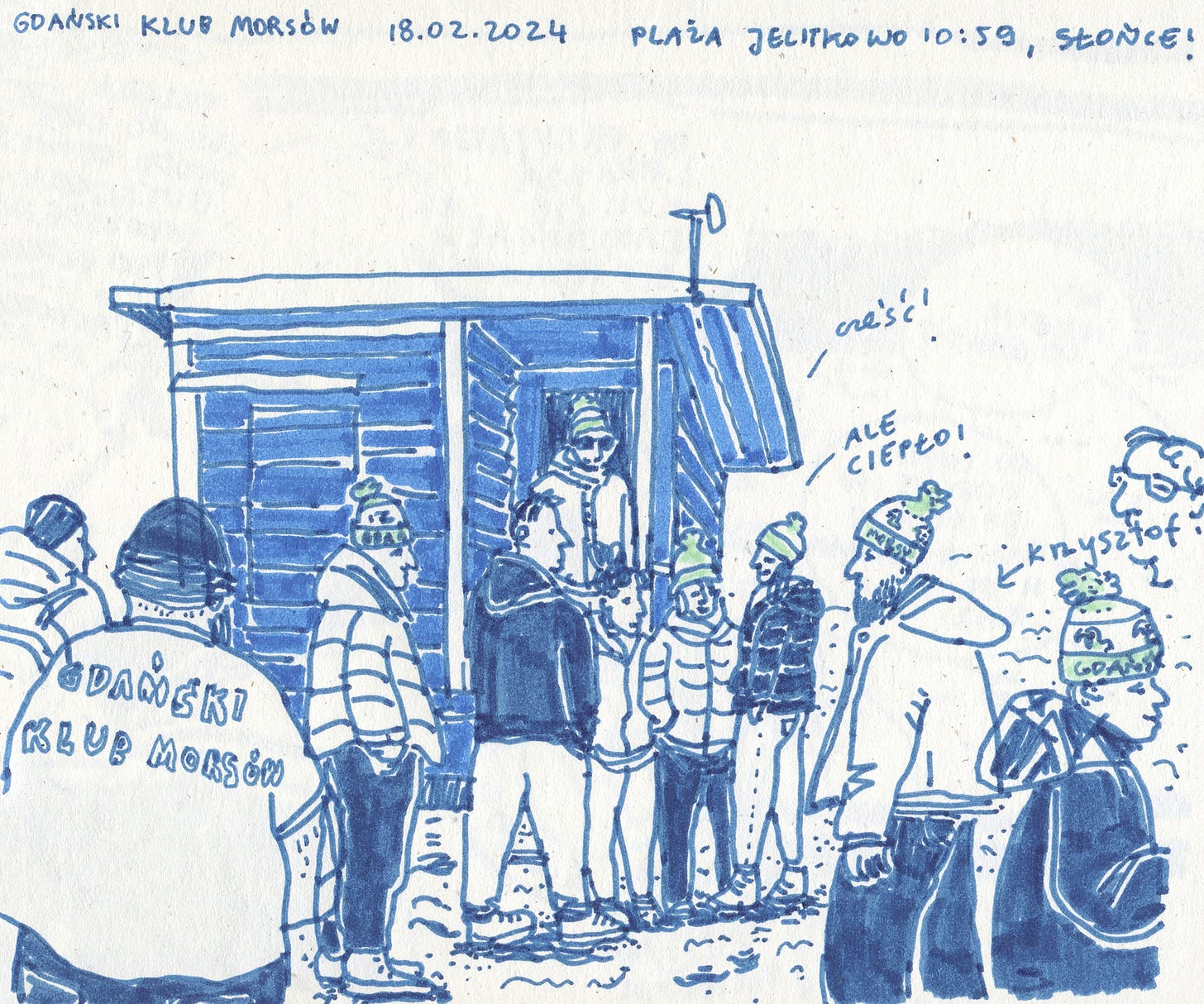

At 11 o’clock on a Sunday morning the temperature hovered at 4 degrees Celsius, and the sun was just about to come out.

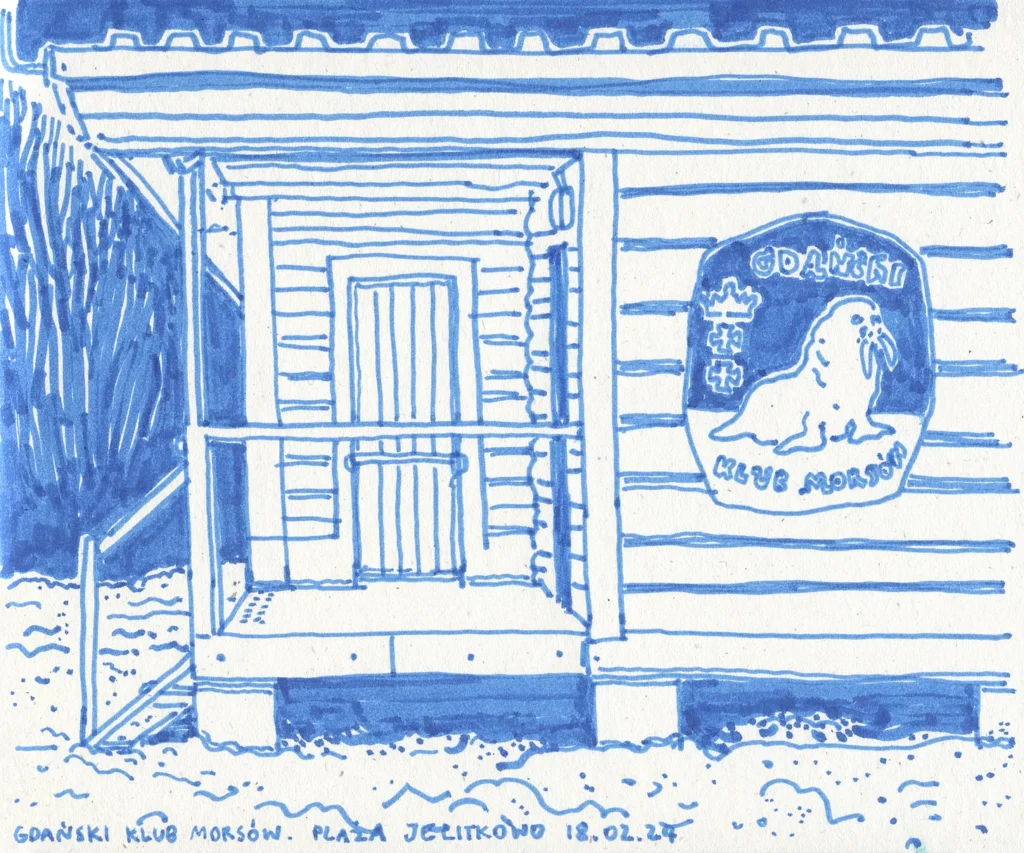

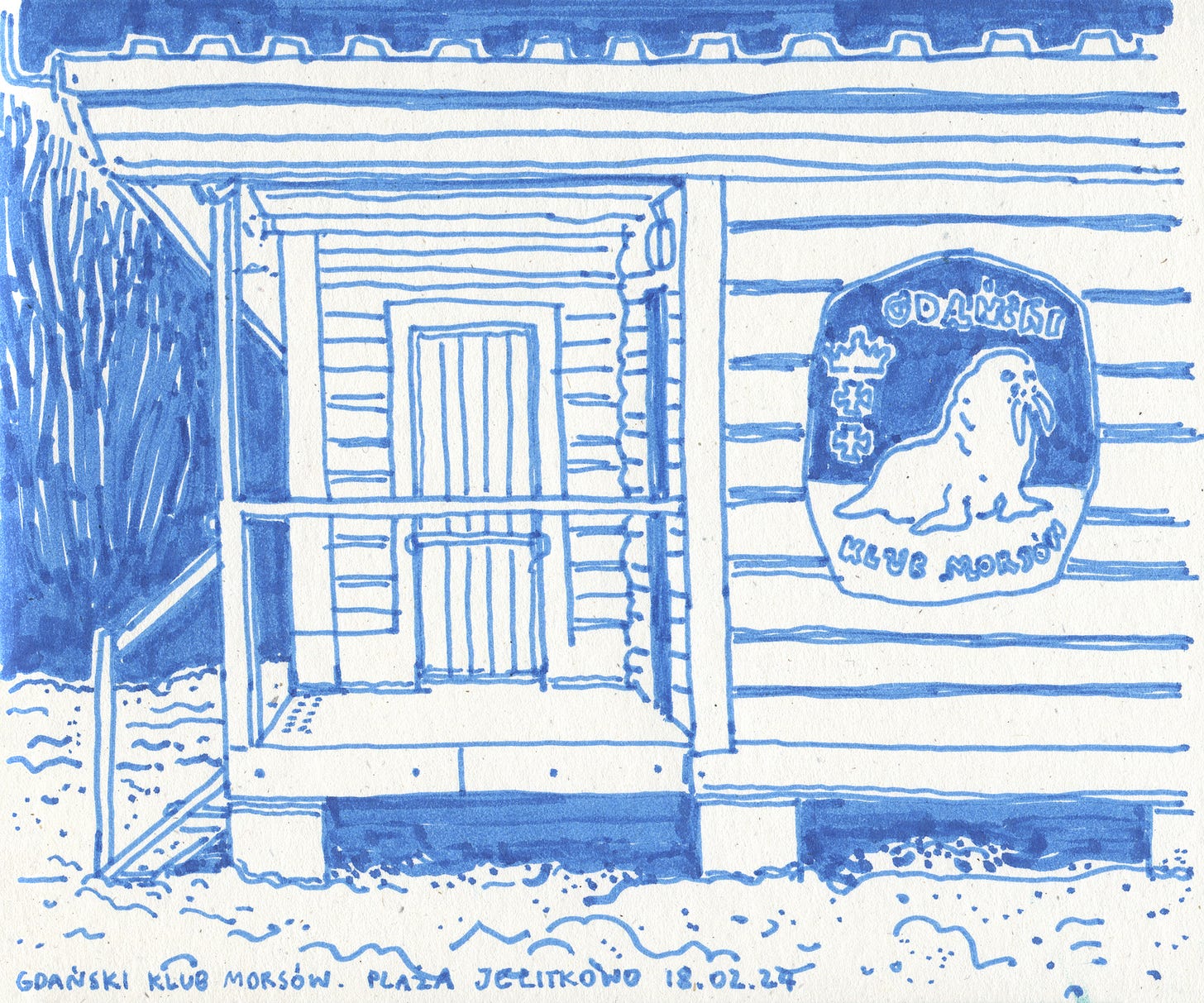

People in blue hats, as blue as the sky, began to gather around a little blue hut on the beach. This hut is the headquarters of the Gdańsk Winter Swimming Club, the oldest club of its kind in the country. They’ve been winter bathing together since 1975, and meet at this very spot each Sunday morning.

The club’s vice president, a tall man named Krzysztof, welcomed everybody at the porch of the hut. Excited chatter filled the air. Scanning the crowd, I saw as many women as men, and as I later found out, the youngest member was 10 years old and the oldest 90.

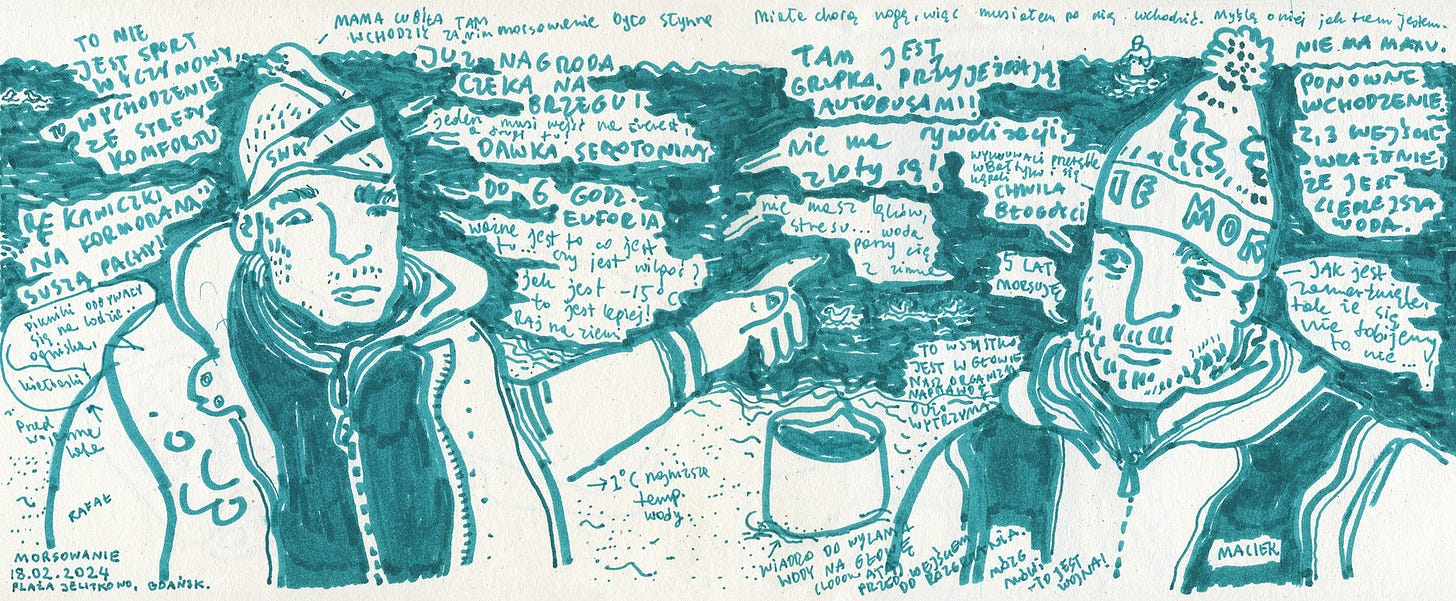

After some housekeeping, Krzysztof introduced Rafal, a knowledgeable walrus who led a special first-aid training session for the group.

“Rule number one: never swim alone,” said Rafał before emphasizing the importance of CPR and having a defibrillator on site. In case of hypothermia, “a great way to quickly increase somebody’s body temperature is to fill up plastic bottles with warm water and stick them into their armpits and groin,” he added.

After the talk, things started happening fast. Sucked into the whirlwind of excitement, I temporarily forgot all about the cold as I watched the walruses warm up.

Ready for the plunge

As a Romanian disco tune that once topped the charts in Europe played through the speakers and set the beat, “Maya hi, Maya hu …” walruses divided into groups and stood in big circles. All together, they moved their arms, legs and hips left and right, up and down, and all around.

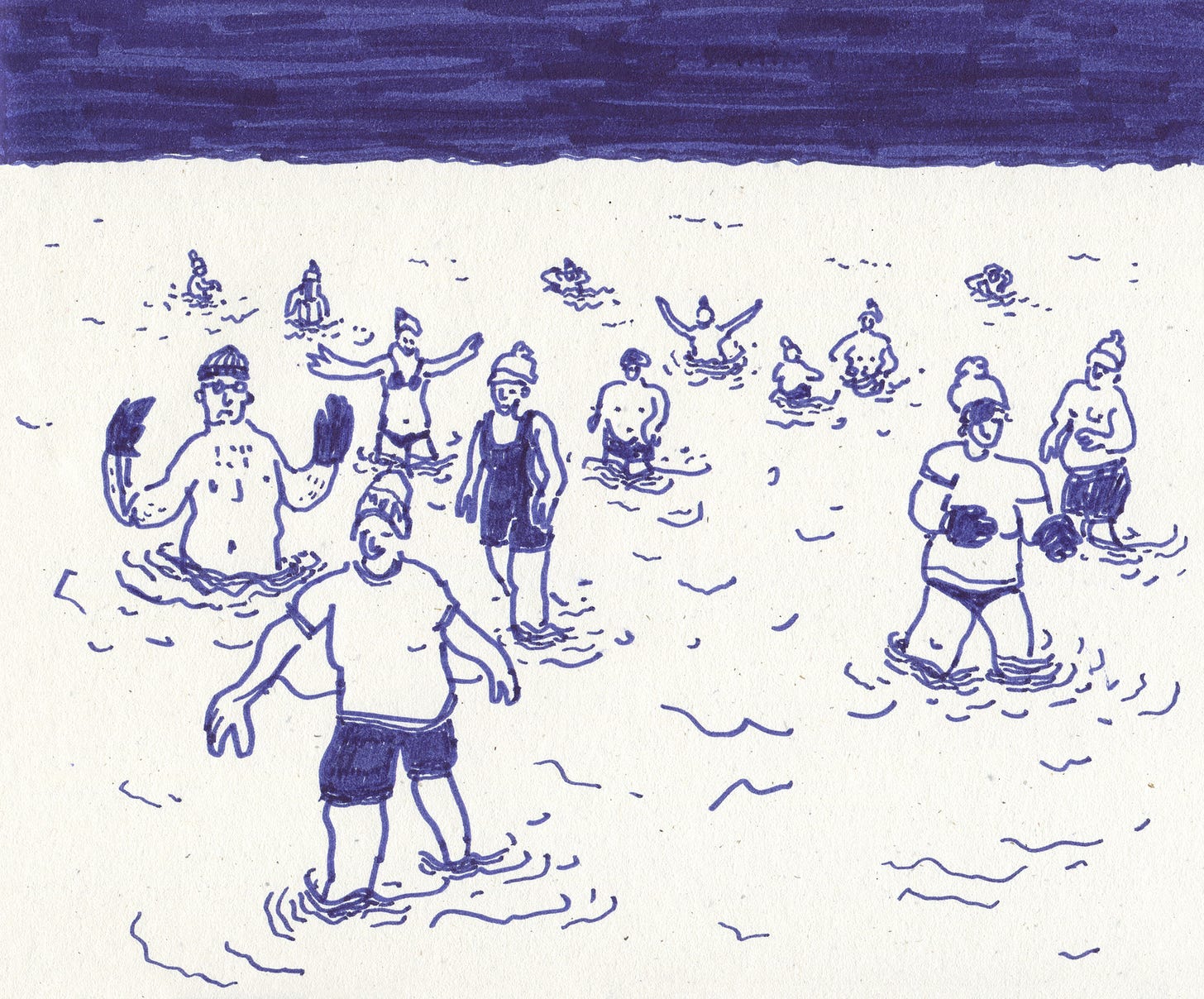

I turned my gaze towards the sea, which was now full of people. The day was so still, there were hardly any waves. An infinite horizon sprawled behind the swimmers in a delicate sunny haze.

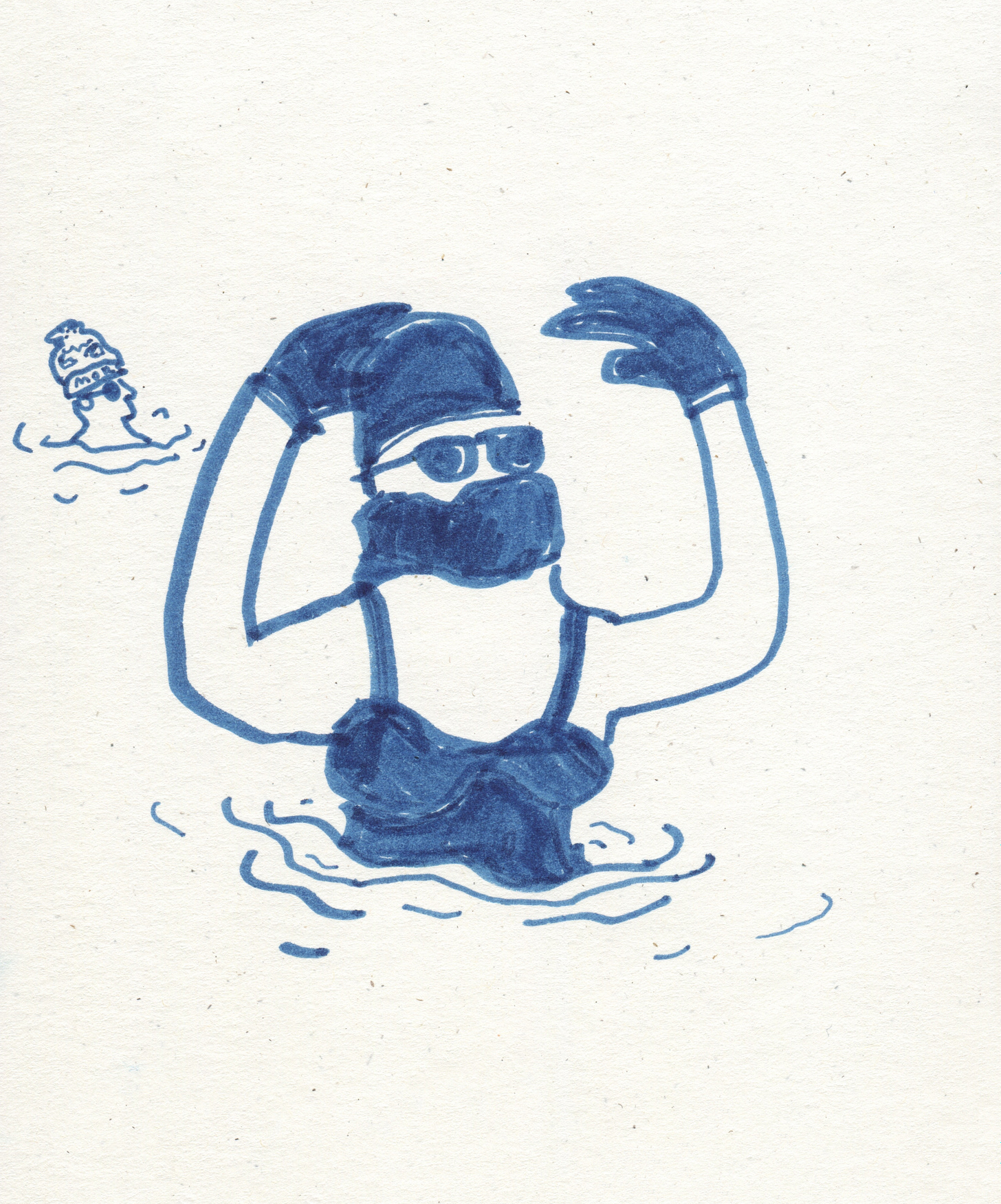

Each swimmer seemed to have their own technique. Some went into the water up to their necks, others not as far. Some wore swimming shoes or neoprene socks, others wore gloves. But there was one thing that everybody had in common: hats. Most heat exits your body through the head, so it’s a good idea to wear one, they said.

People went in and out several times, and on the second and third entry, the water didn’t seem as cold. I learned that a colloquial “cormorant” is a person who goes into the sea with their gloves on. This makes them hold their arms up in a distinctive position, which resembles the cormorant’s wings.

Embracing the cold

Why exactly do people go winter swimming? It’s not necessarily because they like the cold. Many walruses I spoke to at Jelitkowo Beach blatantly stated that they didn’t. Instead, they told me that a plunge into cold water released endorphins which help reduce stress, increase energy and improve blood circulation. There are risks too, like hypothermia, but Krzysztof, the club’s vice president, said that perhaps the most traumatic club event was when a certain fellow walrus forgot to bring a spare pair of pants. We’re not naming any names!

Rafał, the longtime walrus and trainer, spoke passionately about winter swimming. He told me people do it because they want a challenge.

“Some go up Everest, others go in here,” he said, adding that back in the day, when the winters were more severe, it was common to go swimming at minus 15, or minus 20 degrees Celsius. People hacked into the thick and frozen surface of the Baltic and jumped in anyway. “They’d have entire picnics out on the ice, with fire, and sausages on sticks.”

These days it still takes a lot to stop a walrus from entering the cold waters. “Generally if the water is frozen so hard at the surface that we can’t break in, then we won’t go in,” said Maciek, a walrus who’s been winter bathing for five years and stood next to Rafal as I drew their portraits. He explained that the water temperature doesn’t really fall below 1 degree Celsius, even if the air’s temperature drops below zero. Ice forms on the surface, but below, the water is warmer than the air, and these are the most enjoyable conditions for winter swimming, he said.

“Heaven on earth,” agreed Rafał, who also recalled his mom’s love for winter swimming. “She would go into the sea in the winter, before it was trendy … I always had to go in after her to help her out as she had a weak leg. I think of her whenever I’m out there,” he said pointing at the sea.

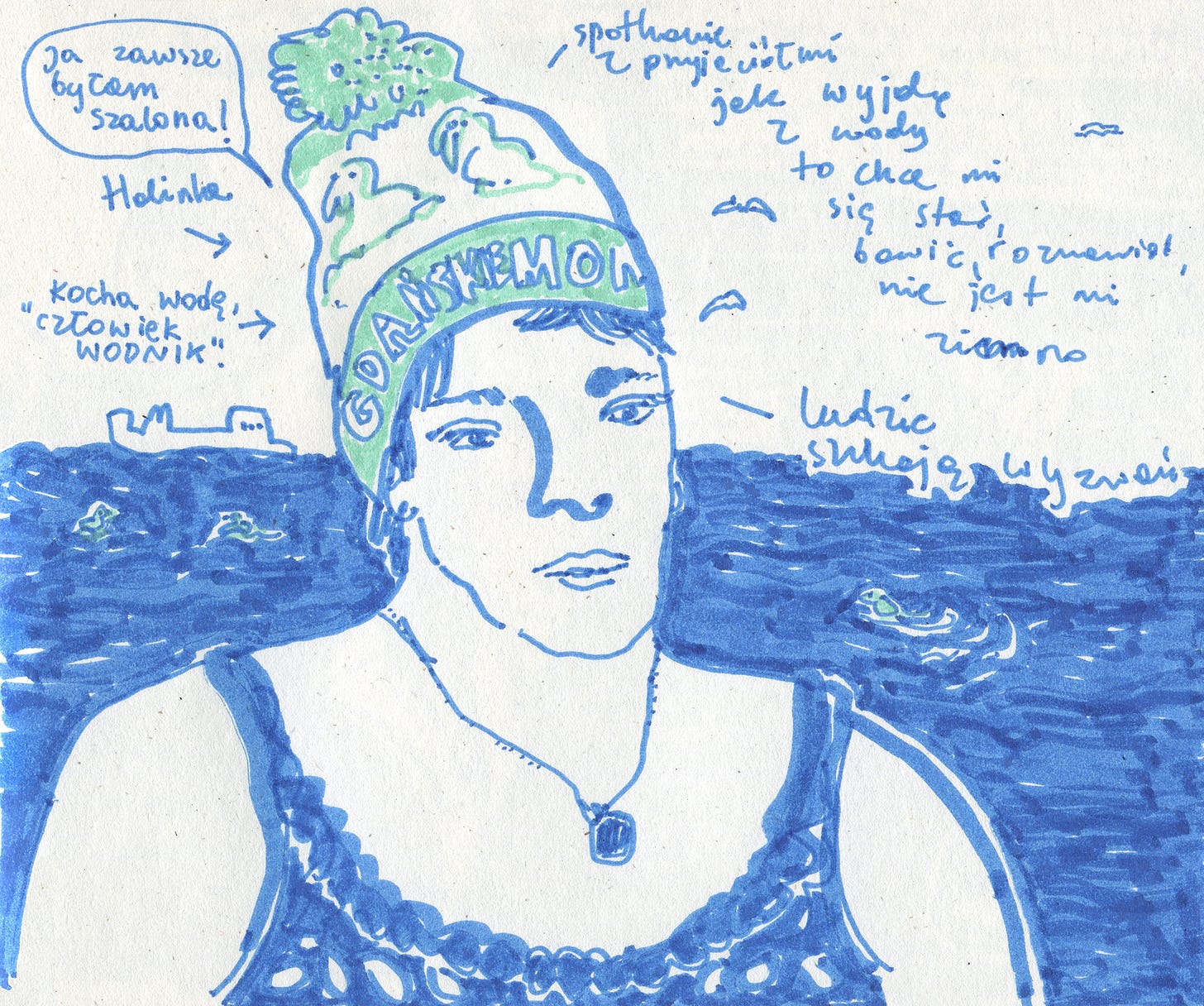

Halina, the club’s secretary and a very warm person, had just emerged from the sea when I approached her. She stood in the sand without an inkling of a shiver, charged with the energy supplied by the sea. She’s been winter swimming for the past 25 years and inspired her son to join her. She loves water, and will submerge herself in it at any given opportunity. She’s always jumping into a lake while mushroom picking in autumn, and describes herself as a “wodnik,” a creature from the Slavic mythology who lives in lakes and rivers.

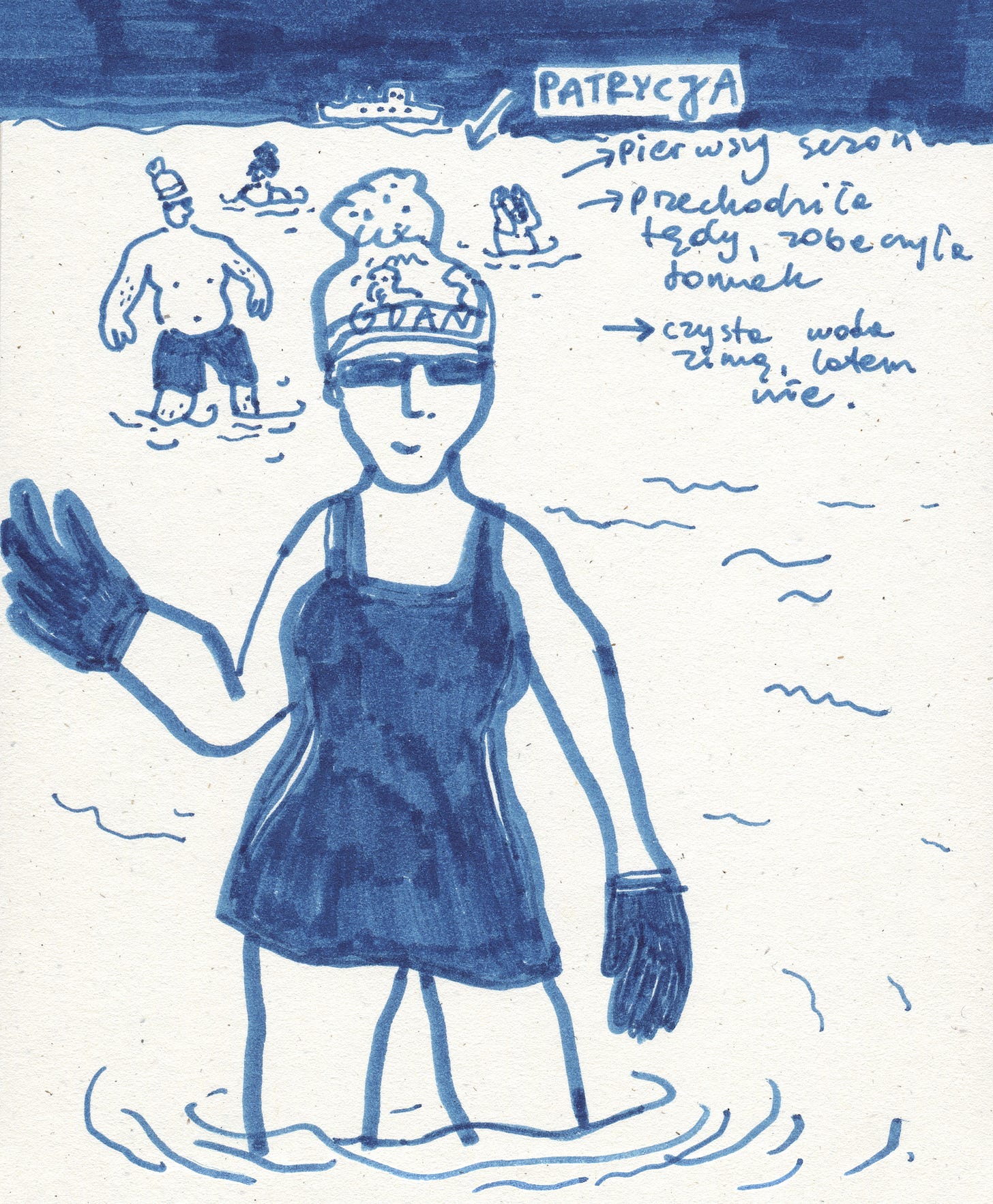

Patrycja, a novice walrus, said she had seen the little blue hut on the beach one day and her curiosity led her to join the club. What else lured her to winter swimming? “The water is much cleaner here in the winter than in the summer,” she said, smiling as she hurried towards the hut to change.

The sense of community and belonging among the walruses is also part of the appeal of winter bathing. Marzena and Tomek come to the club’s plunges once a month all the way from land-locked Katowice, which is about a five-hour drive away in southern Poland. They said if it wasn’t for the club, they probably wouldn’t do it on their own. They’ve been plunging since last October, when they saw the Gdańsk walruses on TV and felt enticed.

While drawing and talking to all these walruses at Jelitkowo Beach in February, I couldn’t help but feel like I was missing out, like I had been let in on a secret that I couldn’t fully comprehend. What is this mystical sensation that is witnessed and shared out there between them all? I realized that I too could probably experience it and find out for myself, if only I’d dared to step into the cold water. Instead, the walruses wrapped me in an emergency blanket seeing that I was cold. “Hey lady, why is your nose so red?” I heard someone shout from beside the blue hut.

Let the winter die

Now it’s March, the sun is shining high in Sopot, and even though it’s only 7 degrees Celsius, it feels much warmer. The water temperature is around 4 degrees Celsius, and everyone is eager to jump in and drown Marzanna. But before they do so, there’s much to happen during this end-of-winter walrus rally, which is organized annually by the Sopot Winter Swimming Club. There’s an aquathon race, a tug-of-war, a contest to name the best Marzanna effigy …

And finally, the singing of the club’s anthem preludes the moment everyone has been waiting for.

… When the frost settles upon Sopot,

the walruses bathe again …

it’s the walruses’ hot blood …

“Plunge, plunge, plunge!” shout the impatient ones from the crowd, holding their flags, banners and Marzannas, as they countdown to the plunge that officially puts an end to winter.

10…9…8…

3…2…1…